literature & citizenship & revolution

this past thursday students and the general public were treated to a conversation with arthur danto, established american art critic, and orhan pamuk, turkish novelist and 2006 nobel prize laureate in literature. the event took place on campus at miller theater, for free, and was part of a series of events being held to recognize vaclav havel's fall residency here at the school. havel is a czech writer and playwright, but in the late 80's he was also one of the leaders of the velvet revolution, the bloodless revolution which at last overthrew the communist government of czechoslovakia in december 1989. havel then retained the position of president of the czech republic. his is a wondrous story, having been imprisoned for years for political activity in theater and the arts.

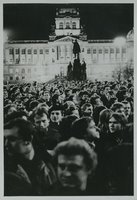

A demonstration on Wenceslas Square in Prague on the twentieth anniversary of Jan Palach's death. Palach was a philosophy student who, on January 19, 1969, committed suicide by self-immolation in protest of the Warsaw Pact force invasion of Czechoslovakia. Two decades later, during what became known as "Palach Week" between January 15th and 21st 1989, thousands of police and militia clashed with thousands of demonstrators. Havel was among several activists who received prison sentences for "hooliganism" during these events. Source: Human Rights Watch Archives, Columbia University (Entry ID: 001005)

A demonstration on Wenceslas Square in Prague on the twentieth anniversary of Jan Palach's death. Palach was a philosophy student who, on January 19, 1969, committed suicide by self-immolation in protest of the Warsaw Pact force invasion of Czechoslovakia. Two decades later, during what became known as "Palach Week" between January 15th and 21st 1989, thousands of police and militia clashed with thousands of demonstrators. Havel was among several activists who received prison sentences for "hooliganism" during these events. Source: Human Rights Watch Archives, Columbia University (Entry ID: 001005) October 1989: protestors in Prague face riot police, shouting, "We have empty hands!" Source: The Charter 77 Foundation (Entry ID: 001023)

October 1989: protestors in Prague face riot police, shouting, "We have empty hands!" Source: The Charter 77 Foundation (Entry ID: 001023)the danto/pamuk conversation ranged widely over various topics from the past and present, but generally focused on the relationship between literature and citizenship, as the title of session intended. at first it seems there is not much of a relationship, purported danto, and wondered what role citizenship plays in countries like the czech and turkey. over the next hour and a half, however, it became clear that a writer is most often influenced by the people and the places and the ideas of his/her country, although the idea and value of citizenship varies from nation to nation. it was also interesting to hear pamuk's journey as a writer: a young man from a wealthy family who wanted to be a painter, but, discouraged by his mother, decided to be a writer; a writer whose father left for paris and lost almost all their wealth; a writer who roamed the earth for decades, writing and smoking, and exploring, partially financially funded by his father until he was 30. he will be writing two more novels as sequels to his latest novel istanbul: memories and the city. pamuk came across as somewhat grumpy, and usually simply responded to danto's questions, never positing any questions of his own; the conversation thus became more of an interview.

pamuk, like havel, seemed like a man with strong convictions. in 2005, pamuk made statements regarding the armenian genocide of 1915-1917, where hundreds of thousands (or perhaps millions) of armenians were killed by the turkish government during the reign of the ottoman empire. he believed the turkish government was hiding the truth from its people in order to preserve turkish nationality. for his statements, pamuk was criminally charged. after much legal action and recrimination, by amnesty and the international community, the charges were dropped in 2006. pamuk has stated that his comments were made to expose the issue of freedom of speech in turkey, where citizenship is thought of, not as an ideal of freedom as it is in north america, but as a duty to the state and a form of obedience. although the belief is true, whether this was his initial intention is anyone's guess.